By Linden Wilkie, 16th December 2022

We’ve had the pleasure of Château Lafleur’s Omri Ram being with us in Hong Kong for a few days recently. After a string of dinners, and masterclasses and I feel I’m beginning to absorb a deeper understanding of what Omri and the Guinaudeau family have been busy doing in recent years. I found it pretty interesting, so let me distill what I learned here as we go through the range…

Two Estates, One Family

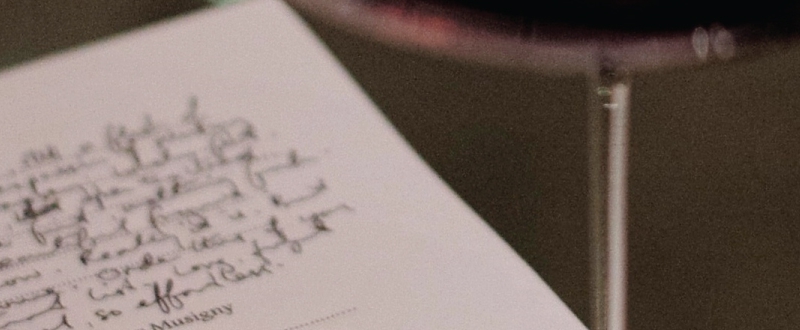

The starting point is to understand that the Guinaudeau family run two properties. Château Lafleur, in Pomerol, was created by Henri Greloud in 1872 around the fine 4.45ha rectangular “garden” vineyard beside the tiny château we know today. It passed down a maternal line to the Robin sisters, the survivor of which brought her young cousin and his wife – Jacques and Sylvie Guinaudeau – in to run the property and make the wine from 1985. (They too were descendants of Greloud). Jacques and Sylvie were at the time already running their own Right Bank property – Château Grand Village, in Mouillac (Fronsac), about 7 minutes by car from Lafleur. Both estates were joined by their son Baptiste and his wife Julie.

This little family story is important because all that they have learned over the past four decades has gradually been incorporated at both estates. The work done today is pretty consistent across the six wines they make today. The 21 hectares total are run by a team of 21 full time people – an unheard of level of labour in Bordeaux. Everything is close by, so the team works flexibly across both properties throughout the year. Nothing is compromised at Lafleur, and neither at Grand Village.

Sylvie and Jacques, Julie and Baptiste, Omri ©Château Lafleur

It's not just grape varieties… it's about genetics.

The “Great Frost” of 1956 wiped out whole vineyards in Bordeaux, and much was replanted with clones recommended at the time. The Robin sisters at Lafleur did not replant, Omri explained. They had heaped up earth at the base of the vines, and took the chance post-frost that perhaps there was still life beneath. Vines were cut down to this level to see if growth would come. It did. It meant that not only did the Lafleurs of the ‘60s and ‘70s come from old vines (more on that next week), it also meant that Lafleur retained vines of a very old local DNA. Bouchet is the name given locally to the very old genetic Cabernet Franc here, and Lafleur calls it that not to be cute, but because they have found it is quite different in characteristics, aromas, and flavours to the nursery-bought clones of Cabernet Franc now widely planted in Bordeaux and elsewhere. Today only Cheval Blanc, Ausone and Lafleur have any real quantity of old Bouchet.

Lafleur has continued to propagate – massale selection – from their own Bouchet (and their own Merlot) – from a large variety of vines at the estate sharing these genes. And, in gradual replanting work they have been doing at Grand Village, they are using this Lafleur genetic material to replace the clones.

©Château Lafleur

At Les Perrières, a new vineyard they have planted on a limestone soil site located between Grand Village and Lafleur, they have planted only Lafleur-derived Bouchet (59%) and Merlot (41%), a mix slightly more Bouchet-dominant than Lafleur. And so here we find Lafleur genetics on limestone terroir. 2018 was the first vintage. The 2019 tasted three times this month, shows succulence and freshness, it has a linear feel, pure and refined, and with limestone-derived minerality. It’s a very elegant wine. It was one of the favourites at our team training, at a session for sommeliers, and at a private client dinner. This is one to lay down, one to watch.

…and terroirs

Château Grand Village sits on a clay-limestone terroir, giving more roundness from the clay, and mineral tension from the limestone. The 2019 red is still young but already more open, softer and more up front than Les Perrières. It’s more Merlot (81%) than Bouchet (19%) driven. I think the quality for the price is exceptional. Grand Village is the great beneficiary of an approach that says 21 people manage 21ha, and the work, and approach in the winery are at the same level. Surely we will see prices here creep up over the years.

The 2019 white, from 74% Sauvignon Blanc and 26% Sémillon is delicious already – super well balanced and fresh, with an aroma and taste of fresh white peach, and a zesty citrus and lemon blossom finish. There’s also real texture here (they use Burgundy barrels), a creamy roundness.

While a lot of work has been done to bring the white to the style they like (more freshness, tension and texture), they also knew there was a limit, so they began a new white wine project on an adjacent plot, called Les Champs Libres. This debuted with the 2013 vintage, and we at The Fine Wine Experience are real fans of this wine. What’s interesting here is that the family sought out a different genetic material to that cultivated in Bordeaux, and found it in an old vineyard in Sancerre. This Loire Valley Sauvignon genetic leads to a more elevated, mineral wine, tighter in shape, more refined still.

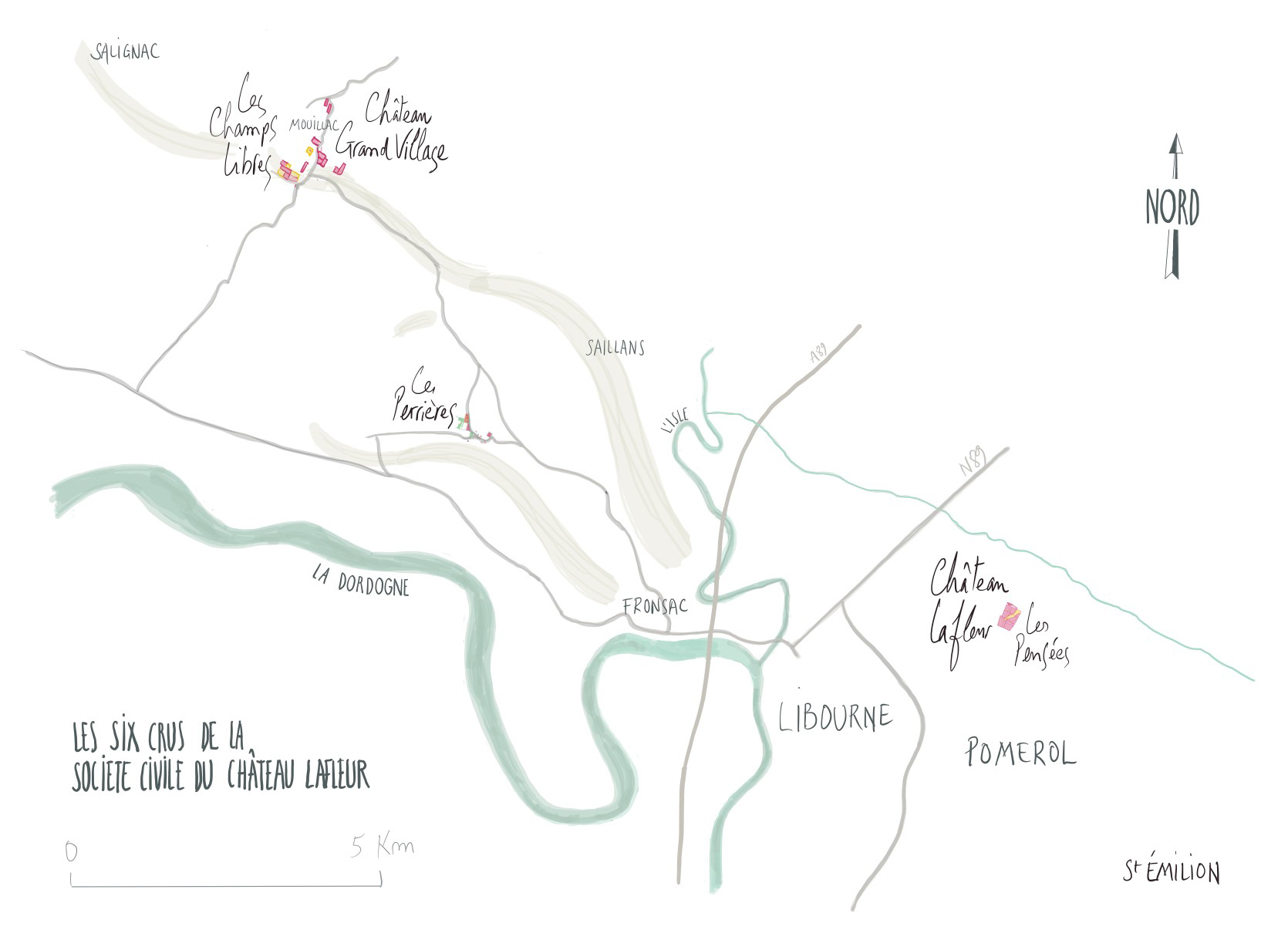

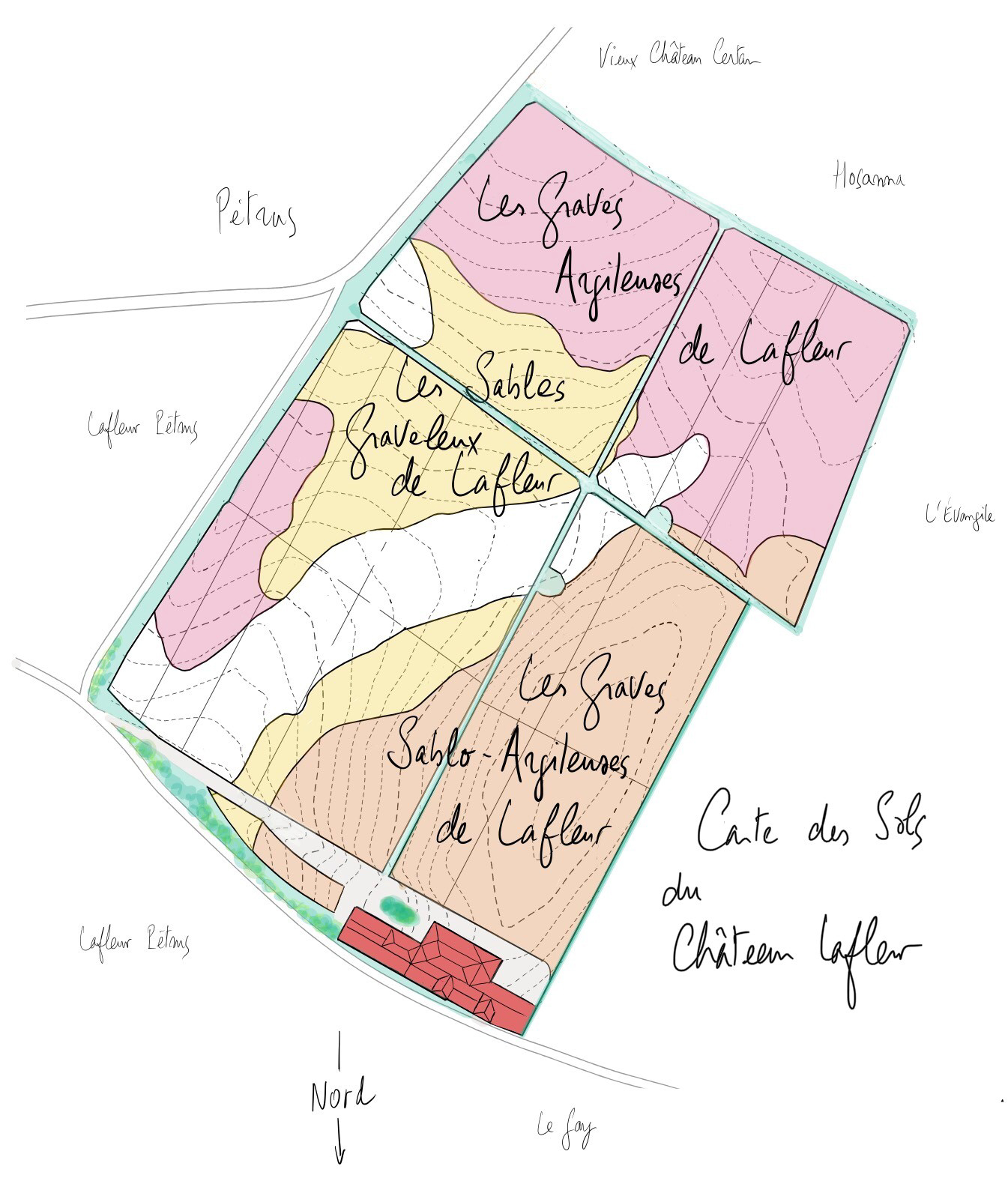

The focus on distinguishing terroir extends to Lafleur itself. Detailed soil maps undertaken in the 1990s led the family to understand better the collection of terroirs in the Lafleur garden, and that led to a change in approach.

Soil map of Les Pensées ©Château Lafleur

Soil map of Château Lafleur ©Château Lafleur

In 1987, in the midst of a very tough vintage, a second label was created at Château Lafleur – it was called Les Pensées. (Ultimately the whole vintage that year was declassified into it). During the ‘80s and ‘90s we can see that this label really was a classic ‘second label’ – a place for young vine fruit, and wine not up to the grand vin quality. But with advances made in the 1990s, and this soil map, the family switched tack. From 1999 onwards Les Pensées is no longer a second label, it is its own grand vin, but from a specific, more humid, more classic Pomerol clay terroir that runs diagonally through the centre of the vineyard in a small depression. It is very similar that terroir found at prestigious neighbouring Pomerol plateau estates (and quite different to the rest of Lafleur). Since 1999 that is Les Pensées. It is a wine of enormous appeal, as we found tasting the 2019 and 2016 this week. It has what Omri describes as the classic Pomerol ‘spherical’ shape on the palate, it is more fragrant, more charming as a young wine. It is also elegant – it is not a thick, heavy kind of wine. It is deserving of its own attention and following, but I feel today it is still a bit misunderstood. This wine – from just 0.7ha – is perhaps too rare to be really understood more widely however. But it is worth the effort – you should try it.

And that leaves the final wine of the six, Château Lafleur, focused solely on its most unique terroir – gravels. There are within the plots varying degrees of clay and sand and stone sizes, but gravel is the key here. It is why Bouchet is so successful here, and so high in the blend (around 50%). That, combined with the old genetics here, and we can begin to understand the enigmatic qualities of this, one of the world’s greatest wines.

Next I will write in more detail about Lafleur, but for now I wanted to convey what I distilled from a few days with Omri in Hong Kong. Perhaps we can describe the Grand Village white and red as – indeed – the “village” wines of the family, Les Perrières and Les Champs Libres as the “1er cru” projects, and Les Pensées and Château Lafleur as the grands vins, the grands crus. A useful, but imperfect hierarchical view. From another perspective we can see six wines, in a sequence of plantings from old (mostly proprietary) genetics, each expressing distinct terroir. Either way there is a place at your table, I hope, to explore each one.